By Jennifer Mustoe and Craig Mustoe

Utah Shakespeare Festival (Utah Shakes, USF) tells us that Trouble in Mind, a play about racism and theater in 1957, “will make you laugh, and make you think.” I will tell you that for me, it did far more. I rarely have had such an enormously profound experience as I did in Monday’s performance of Trouble in Mind. I was, in a word, gob-smacked.

The show begins with Henry (Michael Fitzpatrick), an old Irish techie who now works for the theater probably as a thank you for many years of service. Henry is old, but prides himself on looking younger (can I say spry?) than his very senior age. We like Henry, and Fitzpatrick charms us with his storytelling and familiar, sweet manner. In walks Wiletta Mayer (Yvette Monique Clark), a black woman who knows Henry from way back, as she’s been in the business for years. We like Wiletta, she has confidence, grace, and spunk. As they reminisce, for a moment, we in the audience think–ah, this is going well. We are entertained by their friendship. We are comfortable.

However, as the other characters appear, we begin to see the Trouble in Mind all too quickly. John Nevins (Maurice-Aimé Green) is a new to Broadway actor who’s graduated with a degree in Theater and had played summer stock. In other words, he’s a talented and educated black actor. Millie Davis (Cherita Armstrong) is a spitfire of a young black woman, married to a man who may or may not have money, so she’s acting for “fun” or for the love of theater that so many (of us) actors have. These two young black actors are the opposite of one another, he an educated, well-spoken man, she a forthright, outspoken, sassy actress with no structured education. Both of these young people are beautiful, highly talented, and amazing onstage. Antonio TJ Johnson plays Sheldon (Shel) Forrester, a fine, old actor, comfortable in his stereotypical roles. It’s all he’s known. He is the opposite of Wiletta, who begins to realize that there is more to stage work than being the token black mammy. He accepts it, she fights against it.

All the black actors start to instruct newbie John on how to behave with the white director, who has yet to appear. John is horrified with their advice, to laugh and agree with everything the director says, do whatever he says, no matter how abhorrent or embarrassing or degrading it is. Be “Uncle Tom” with a big smile. Not only is the advice insulting, it also means John can’t be authentic as an actor. As Wiletta says, “This is show BUSINESS,” and they’re all here to act, but also to get by and get through it. Millie says that in one whole play she repeated, “Lord, have mercy” while waving her hand in the air. Shel reiterates all that’s been said: play the part they want you to play, which is usually the po’ black slave; he just wants to make enough to pay his rent and his bills.

In breezes Judy Sears (Bailey Blaise) a young, inexperienced actress, a Yale graduate agog with being cast in the show. She’s just so clean and starry-eyed with her blonde hair and sweet smile. She, simply by being white, is the opposite of all the black people on the stage. Guileless Judy sees her fellow castmates as people, not black people, unusual in 1957. Recognizing immediately the inequity that is developing, she silently apologize for her entitled status, opposite of all who stand on the stage with her.

Director Al Manners, an abusive King of Isms: racism, ageism, sexism, elitism, a predator who constantly rages at and victimizes everyone finally appears. Rex Young embraces Manners’ truly despicable behavior. In one crushing moment, Manners completely decimates Stage Manager Eddie Fenton (Jeremy Thompson). Eddie stands center stage, still, holding back the tears. Manners brags he could be directing a big TV show in California, but decided to support the negroes’ cause by directing this black show. It made me wonder–is Manners really just unable to get another job because he’s such a creep? It seems unlikely that he’s so dedicated to the cause. Bill O’Wray, played by Chris Mixon, completes the cast playing a Southern slave-owning plantation owner, the stereotypical Southerner who stands for his representation of truth.

Wileta is at once confused by Manners’ perplexing stage directions, and in one glorious scene, Clark glows and scorches as Wiletta makes up her mind that she will be an actress, an ACTRESS and not what people expect her to be. Things come to a head when she realizes that her character is asked to do something that Wiletta knows is completely wrong. The climax of the show knocked me off my already wobbly emotional balance–no spoilers here. I walked out of the theater literally shaking and it was hard to catch my breath. When I mentioned this to an actor friend of mine, he said, “That’s great!”

I saw Trouble in Mind as a series of conflicts and opposites: black and white, young and old, educated and learning through “hard knocks”, acting for art and acting as a job, kind and abusive, outspoken and quiet, inexperienced and professional, truth and deception, authentic and phony, male and female, then and now. Another theme that permeates Trouble in Mind is how far are we willing to go to see real change? Is it better to take a few “safer” steps, or go for broke and perhaps lose everything?

Playwright Alice Childress has built each scene with her finely crafted characters, and it is, in fact, far more humorous than one would imagine, far more sharp and stinging, and all too painful in many instances. She represents the black experience with deftness, raw clarity, comedy, darkness, and inevitability. It wounded me. It moved me. It changed me.

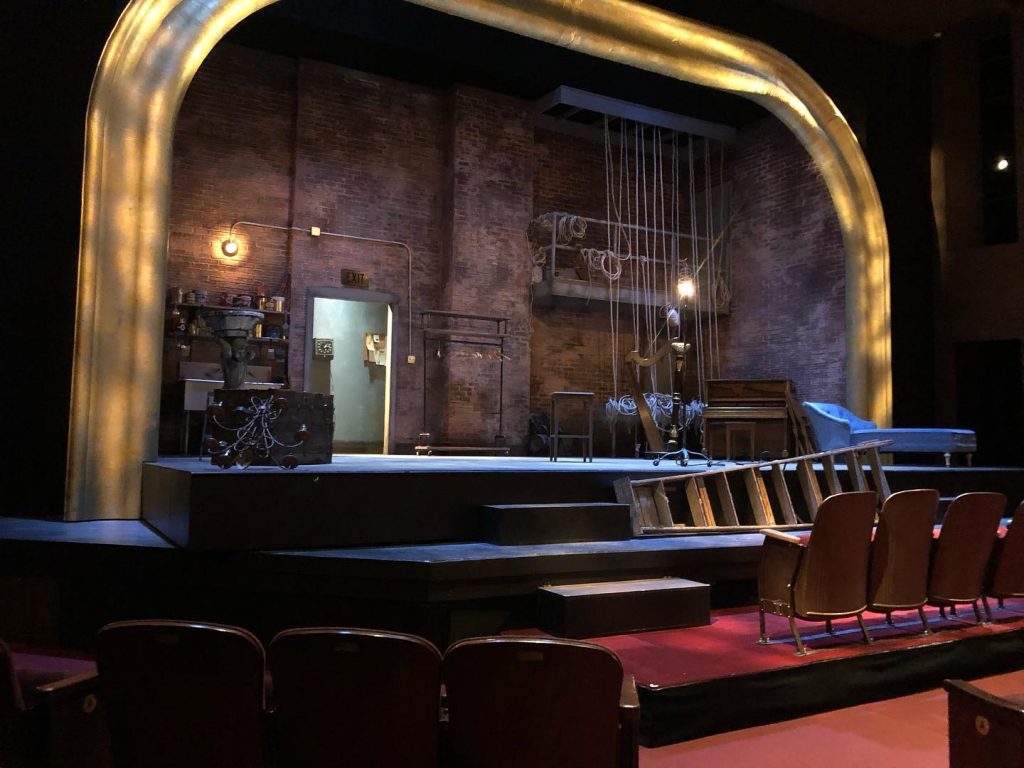

Director Melissa Maxwell keeps the tension high with her talented cast. The beauty, humor, reality flows over us, but pins us to our chairs, too. The delicious costumes by Myrna Colley-Lee are a delight. Millie is the height of fashion, Wiletta is stylish and classy, John has panache, Shel is comfortably attired, Judy is young and current, Henry dapper in his old time theater garb, and Mixon handsome and aloof. Lighting Design by William Kirkham and Scenic Design by Jo Winiarski are brilliant. It’s almost as if dust has been piped in to help us appreciate the space. The worn brick walls, thick, ancient ropes hanging from the ceiling, the upright piano are settled in for the long haul. Sound Designer/Original Music Composer Michelle Chen Cole brings the perfect addition to help us understand that this takes place in the late 1950s but feels familiar, fun, reminiscent. Beautiful. Dramaturg Ashley M. Thomas prepared her actors and we reap the benefits. Everything feels authentic.

Though there are some difficult, painful, realistic aspects to Trouble in Mind, don’t miss it. I’d suggest audience members from age 11+ will understand and appreciate it. The messages in this play are critical and necessary in our community, country, and world today. Utah Shakespeare Festival brings us a timely piece that will give you plenty to talk about on your drive home, and if your experience is like mine, you will think about Trouble in Mind with honest self-reflection for a long time.

Utah Shakespeare Festival presents Trouble in Mind, by Alice Childress.

Randall L. Jones Theater, 351 W. Center St. Cedar City, UT 84720

Plays until September 9, 2022, times and dates vary.

Tickets: $29-$84

Contact: 800-PLAYTIX (752-9849)

Utah Shakespeare Festival Facebook Page

0 Comments